GLOBAL warming is a fearsome proposition, dredging up visions of rising tides engulfing shoreline cities, and other cataclysms. For winemakers, especially those in historically cool grape-growing regions, the changing climate has already markedly affected their lives and wines.

''This has been great, no doubt,'' said Johannes Selbach, speaking by telephone last week from Zeltingen, Germany, where his family has grown grapes along the Mosel River since the 17th century. ''Just look at the row of fine vintages we've had. From 1988 through this year it has been strikingly warmer than any time I can remember. Everybody talks about it here.''

Wherever winemakers have historically struggled against the elements, hoping to coax just enough warmth from the cosmos to release the sugar inside the grapes and achieve ripeness, the last decade seems to have brought little but blue skies.

In Germany, the run of good and great vintages since 1988 has been, as Mr. Selbach said, unprecedented. Piedmont in northwest Italy had a great vintage every year from 1995 to 2001. In Oregon, the run of excellent vintages began in 1998. In Champagne, where single-vintage bottlings were once the exception, done only in the best years, vintages were declared nine times in the decade from 1990 to 1999, as against six in the 1980's and four in the 1970's. That increase may in part be because of the higher prices the Champagne producers can demand for vintage bottles; greed may have been inflamed by the bigger, riper grape harvests.

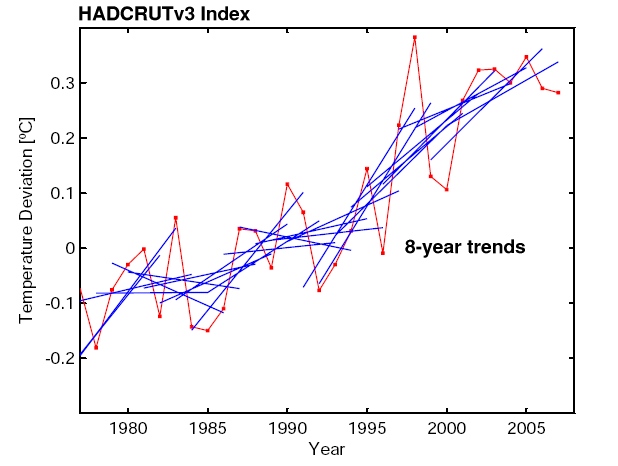

While scientists and politicians debate the reasons for global warming, the gradual heating of the atmosphere is well established. Temperatures around the world have on average increased about one degree Fahrenheit since 1900, said Jay Lawrimore, chief of the climate monitoring branch of the National Climatic Data Center in Asheville, N.C., which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. While that doesn't sound like much, it also doesn't tell the entire story.

''The real issue is, there are increases that are much above that in different parts of the world,'' Mr. Lawrimore said. ''In Alaska, it's been about five to eight degrees higher. It's higher in higher latitude areas. The real concern is, not what's happened already, but what's going to happen in the future.''

For winemakers, though, what's happened already has bordered on the miraculous. In the hilly vineyards of Piedmont, Barolo and Barbaresco, producers reserve their best south-facing slopes -- the ones where the snow melts first -- for nebbiolo vines, so that the grapes can absorb every last bit of sunshine in their annual battle to ripen. Each year, historically, was a roll of the dice. Maybe, just maybe, the weather would warm enough and the rains would hold off. But after a few below-average years in the early 90's, 1995 was very good, and '96 was great. So were '97 and '98, all the way through 2001. Nobody in Piedmont could recall anything like it.

To Angelo Gaja, the superstar winemaker, the climate was clearly the reason for the great vintages and the great wines. ''Since 1996, the spring has started maybe 20 days earlier,'' he said in an interview earlier this year. ''We started the harvest in the end of September and not in the end of October as we did in the 70's and 80's. The influence of climate and light was different, and that's why you have the impression of a complete taste that in the past we didn't have.''

Even in such seemingly charmed times, no farmer can take the weather for granted. Sun today is no insurance against disaster tomorrow. In 2002, a late summer hail devastated grapes in the Barolo region.

''Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get,'' said Robert Pincus, a scientist at the Climate Diagnostics Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder. ''It's a statistical issue. Winemakers are used to weather changing. Nobody's used to climate change.'' Dr. Pincus, who is also a wine lover, wrote an essay this spring on wine and the changing climate for Gastronomica, a journal of food and culture published by the University of California. While he acknowledged that winemaking was flourishing in cooler areas warmed by the changing climate, he foresaw danger in areas where wine production is closely tied to the current climate. He predicted that German ice wine and Austrian grüner veltliner, both of which depend on a chilly climate, may become much more difficult to make.

In an interview, Dr. Pincus speculated that winemakers all over may have to discard time-honored techniques for new methods. ''I think with climate change the wines from, say, Côte Rôtie, may be beautiful, but they may be different,'' he said. ''What the winemakers know about making Côte Rôtie for seven generations, may not tell them everything they need to know in the future.''

While the climate change has not yet been so radical, winemakers are already tailoring their methods to the new, warmer reality. Odilon de Varine, winemaker for the Henriot Champagne house in Reims, said the problem in the vineyards is no longer praying for the grapes to ripen but preventing them from ripening too much. Good Champagne requires high acidity, which contributes liveliness and verve. As the sugar increases in ripening grapes, the acidity drops. ''If the grapes get too ripe, it is not Champagne,'' Mr. de Varine said.

Partly because of the weather and partly because of changing public tastes, Mr. de Varine said, Champagnes of today differ from Champagnes of the past. ''If we had Champagne like it was 20 or 25 years ago, nobody would understand what it was,'' he said. ''It was more acidic. Now it is more fruity, with more body.''

Though it's tempting to cite climate alone, other factors have led to improved wines. In Champagne, better vineyard techniques saved Veuve Clicquot's 1995 vintage from mildew, said Frédéric Panaïotis, a winemaker there. Thirty years before, he said, the harvest would have been lost.

Along the Mosel in Germany, the wines have only changed for the better. For years, the best grapes were classified according to ripeness at the time of picking. Those with the least amount of sugar were called kabinett, while grapes with more sugar were called spätlese, auslese and on up the scale. From the late 1980's until last year, when the sugar standards were raised, no true kabinetts were made, said Ernst Loosen, whose family has been making wines along the Mosel for 200 years. The grapes were ripe enough to be called spätlese, he said, but were declassified and used to make kabinett.

The great benefit of the warmer weather, he said, is that consumers are learning what to expect from German wines. ''It's one of the reasons we do so well now, because we can consistently make great wine,'' Mr. Loosen said. ''This used to be possible only once every decade.''

Still, as Dr. Pincus warned, German ice wines, in which grapes are left on the vines until they freeze, are becoming more difficult to make. If the frost doesn't come early enough, the grapes can rot. ''We still get frost,'' Mr. Loosen said, ''but it is only one or two or three days maximum, and on that day we have to hit it.''

Not all wine-producing regions have been affected by global warming. In the Napa Valley, which has almost always been warm enough that ripening grapes has rarely been a problem, winemakers have detected little evidence of climate change.

''I don't think we're getting global warming here, at least not that we've noticed,'' said Bob Steinhauer, vineyard manager for Beringer Blass Wine Estates. ''We wouldn't want it to be any hotter, I'll tell you that.''

Nor has global warming affected the Finger Lakes region in New York, said Willy Frank of Dr. Konstantin Frank's Vinifera Wine Cellars in Hammondsport. Mr. Frank attributes the stable climate there to the moderating effect of the deep Finger Lakes, which tend to cool warm air and warm cool air. And in Australia, where drought has been a concern for several years, winemakers have yet to see a pattern of climate change, said Peter Hayes, a senior viticulturalist with Southcorp Wines.

But in Oregon, a higher latitude than California, it's hard to find a winemaker who won't swear that the climate has warmed. ''In Oregon, the saying used to be you got two really good vintages in 10 years, and in the last 10 years we've probably had nine,'' said Lynn Penner-Ash, who specializes in pinot noir at Penner-Ash Wine Cellars in the Willamette Valley.

Riper grapes than she has seen in her 15 Oregon vintages have caused her to rethink her wines in the last few years. ''Wines from cooler vintages tend to have brighter, redder, more focused fruit,'' she said. ''These tend to have a darker, jammier fruit.''

While Ms. Penner-Ash is concerned that the reputation of Oregon for making lean, elegant pinots might change as the wines become more powerful, she says the benefits of a warmer climate are clear.

''Oh definitely, it's been fun and easy on all the winemaking and vineyards,'' she said. ''The last couple of vintages have been much easier to sleep through.''

Photo: NOT SO CHILLY -- A warmer climate in recent years in the historically cool Mosel River valley in Germany has made it easier for grapes to ripen. Left, a vineyard above the town of Bernkastel-Kues. (Photo by Jim Marshall/Envision)(pg. F2)