BEGIN TRANSCRIPT

RUSH: Evan in West Coxsackie, New York, welcome to the EIB Network. Hello.

CALLER: Hey. I'm just wondering, when you listen to music with your hearing aid, how's it sound?

RUSH: Music?

CALLER: Yeah, like if you're listening to music on an iPad or something?

RUSH: Well, not very good. I cannot listen to music that I've never heard before and identify the melody.

CALLER: Oh.

RUSH: I have a cochlear implant. It doesn't have nearly the sensitivity of the human ear, it's not even close.

CALLER: I was just wondering.

RUSH: Like violins or strings sound like fingernails on a chalkboard to me.

CALLER: Oh, well, I was just wondering.

RUSH: What I have to do, I can still listen to music, but it has to be music that I knew and that I've heard before I lost my hearing. And what happens is that my brain, fertile mind, provides the melody. I actually am not hearing the melody, and the way I can prove this to you, sometimes it will take me, even a song that I know, it will take me 30 seconds to identify it if I don't know what it is. Now, if I'm playing a song off iTunes and the title is there and it starts then I can spot it from the middle, but if I'm listening to a song from the beginning, and I don't know what it is, it sometimes can take me 30 seconds to recognize it, if I knew it before. But the quality of music that I hear is less than AM radio, in terms of fidelity. I can turn the bass up on an amplifier and I don't hear any difference at all. I can feel the floor vibrate, but I don't hear any more bass. I can turn highs up and I can hear the difference in the highs, but on the low end I actually cannot -- (interruption) I'm getting a note here that says: "You're not missing anything. There aren't any melodies in music today." (laughing) At any rate, you adapt to it. I've adapted.

The worst part of my hearing is being in a crowd. Like right now, I hear myself as well as I heard myself when I could hear. If I'm talking to one other person in a quiet room I can comprehend 90-95% of what they say depending on how fast they're speaking. There are some words that sound alike. But you add room noise, like if Kathryn and I are watching TV and she wants to talk to me about what we're watching, I have to hit pause or the mute 'cause I cannot hear what she's saying. Even if she's sitting two feet away I will not hear as long as there are other noises there. Any room noise when added to other room noise is gonna be louder than the one voice that I'm trying to hear. I've got the implant on my left side so if we go out in a public place, anybody on my right side, it's hopeless. I'll have to literally turn to them, and sometimes as I turn to them they turn with me. They don't know what I'm doing so we'll do pirouettes 'til I finally say, "No, you stay where you are. I'm trying to position my ear so I can hear you."

The way I look at this, though, because when I tell these stories, "Oh, that's really horrible." No, it's not. 'Cause if you look at the timeline of humanity, however long it is, 10,000 years, a million, billion, whatever the number is, my little time on it is not much larger than a grain of sand. And yet I happen to lose my hearing at the same time technology had evolved to the point where cochlear implants had been invented. If I had lost my hearing 15 years ago, it would have meant the end of my career. I would not have been able to hear. And the doctor said you might think that you could speak normally just by virtue of memory and feel, the way voice feels when you speak, but eventually your speech would deteriorate, and it would sound to people as though you had a speech defect. It would just be automatic no matter how good you are, no matter how professional you are at it. So that's really fortunate. It's almost miraculous that my being afflicted with this autoimmune disease happens to coincide with technology. Some call it divine intervention. Some call it the age of miracles. We're all one way or another part of this age of miracles.

Music is the one thing that I miss, but you know what else? This is another thing. Compatibility with other people in normal circumstances takes a big hit. For example, my most comfortable is sheer quiet now. The ringing of a phone or I'll be sitting in my library and there will be a noise. I remember we had been working on the alarm system, and I hadn't been told we were working on the alarm system and every 30 seconds something in the room would beep. I said, "Oh, my gosh, it that the smoker detector, what the hell?" I'd have to call somebody in the office and say, "Where is this coming from?" because I couldn't tell where sound was coming from and I had no idea what it was. One time the phone was left off the hook and there was street noise, it was the phone at the gate. And it was street noise, but it didn't sound like street noise to me. I don't even remember what it sounded like, but I couldn't pinpoint what it was. The phone was still on the hook but the mute button on the speakerphone was off so I had no idea where it was coming from. I had to call somebody in and say, "What is this, where's it coming from?" 'Cause you always worry about something blowing up when there's a sound that you don't know.

But I crave silence, blessed silence because anything other than speech is just noise. It is irritating noise. Well, most people go crazy in quiet environments. They don't like it. Most people love having the TV on in the background or some sort of sound or other. It irritates me. It irritates the heck out of me because it's just noise and I can't identify it. I know if it's noise on TV, but I can't tell you what somebody's saying. I have to have closed-captioning to understand everything being said in a TV program, particularly if there's a music soundtrack. And very few people use closed-captioning. It distracts them. Me, I need it. (interruption) No, I'm not just getting old and cranky, Snerdley. And going in public to a restaurant is, depending on the place, it is impossible. It literally can be impossible to have a conversation except with anybody on the left, and at some places I have to get within an inch of what they're saying to be able to comprehend. I hear everything, but making sense of it…

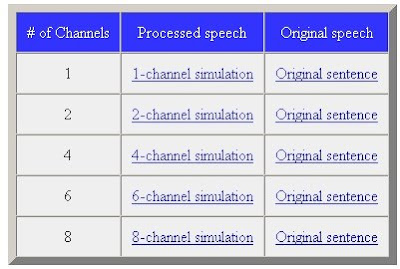

See, the human ear has 35,000 hair cells in each ear. They're microscopic. But they still are different sizes and widths, lengths, and they vibrate. When they sense noise, sound, whatever, they start the whole process of energy through the audial nerve. Well, the autoimmune system killed all 35,000 hair cells in both ears, so they're laying down. They're still in there, but they're laying down. Cochlear implant, I've got eight electrodes, and I'm actually now down to six because two of them were causing facial tics when the volume got too high. My eyes were closing, I looked spastic. I had to deactivate two of those electrodes, so I'm down to six. So I've got six manmade bionic electrodes trying to do the job of 35,000 or 70,000 hair cells in terms of frequency response and all that, and there's no way, it just can't be done. (interruption) No, the technology has not improved. Now what has improved is, like this Esteem thing that we talk about, if you have residual hearing, that's miraculous. The hardware hasn't changed. There are some software improvements.

For example, with the implant I have there's a program called High Res, which activates 20 electrodes. But it doesn't work for me. Everybody is different. They turn on those 20 electrodes -- I got 'em in there -- you turn on the 20 and everybody sounds like the chipmunks to me. It's worse. And that's the digital. I'm using the analog. Everybody that has one of these things has a different experience. Everybody says you need to get one on your right side now. I kept the right side clear because there might have been a cure for these dead hair cells. Now I've been told there won't be. So if I get an implant on the right side that would solve some of the spatial stuff and it would enable me to hear people on my right side if I'm in a public place or what have you. Music, it's amazing what the memory can do when I'm listening to music that I love, that I've known. In fact, I can create the music without evening hearing it. Your memory, your mind can do that.

BREAK TRANSCRIPT

RUSH: Look, folks, don't get the wrong idea. Having a cochlear implant has a lot of positives. I was out playing golf the other day with a bunch of guys, and there was a loudmouth crow in a palm tree right on the tee box, no more than ten feet above us. The thing was cawing like crazy. You just wanted to grab something and throw it at the damn bird to shut up, and it was screwing everybody's tee shots off. I mean, you can't concentrate. The guys would swing and right at the moment of impact, "CAWWW!" and you could just see the effect.

All I did was take my implant off, gently place it on the ground, and total silence. No distractions whatsoever. However, I do have tinnitus (some people say tinn-i-tus) in my right ear -- which, in my case, I constantly hear Gregorian chants. That's the noise in my right ear, but I've got so used to it I don't hear it unless I stop to focus on it, but it's always there. I always think I'm in touch with God. Gregorian chants are constantly going off in my right ear.

END TRANSCRIPT

)

)